Lazy Eye (Amblyopia): Everything You Need to Know

What is Amblyopia?

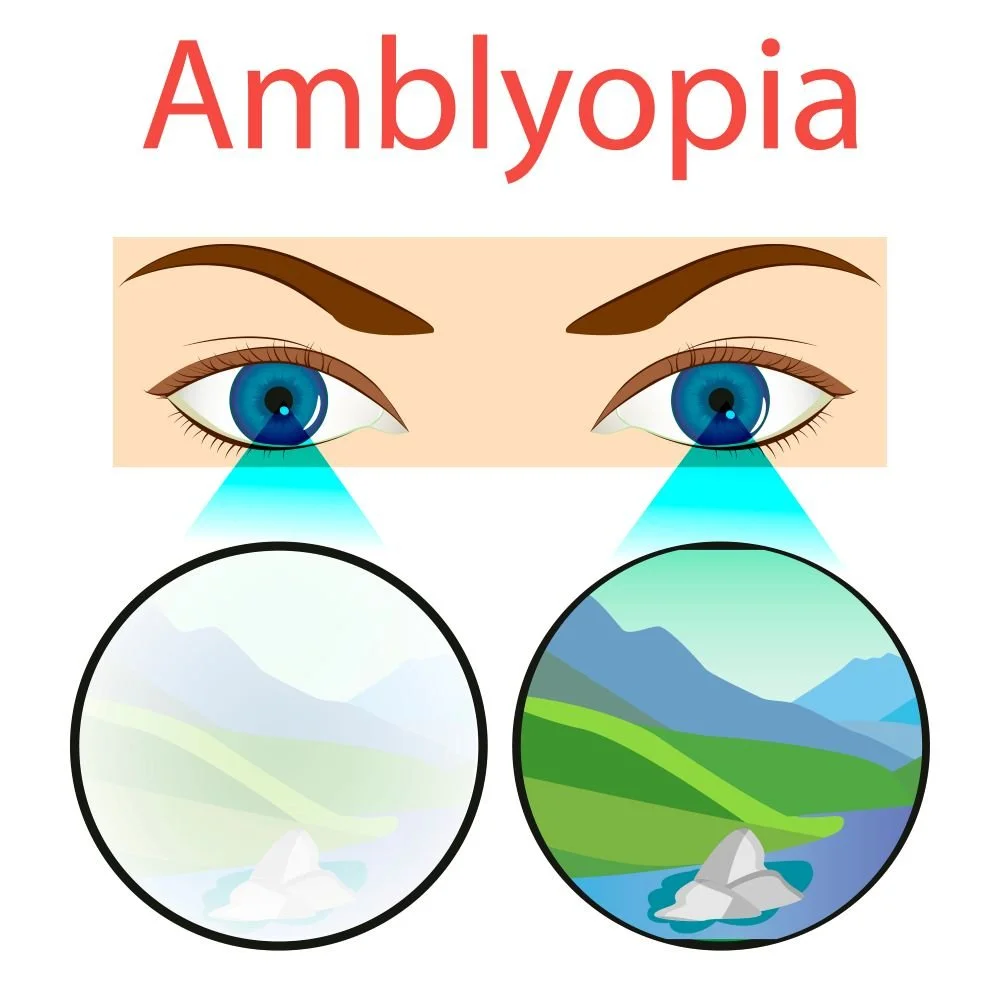

Amblyopia, commonly also known as “lazy eye,” is a visual development disorder that reduces visual acuity in one or both eyes due to abnormal binocular interaction.

It typically occurs during early childhood, within the critical period of visual development, from birth to around 8 to 10 years of age, when the brain is highly neuroplastic and therefore more susceptible to visual compromise.

If left untreated, amblyopia can lead to permanent and irreversible vision loss. The term “lazy eye” can be misleading, as the condition does not necessarily involve an eye that turns; rather, it refers to reduced vision that causes one eye to be weaker in terms of vision than the other.

However, in cases of strabismic amblyopia, an eye turn is (or will be) present.

Types of Amblyopia:

Strabismic: Caused by misalignment of the eyes (turning in, out, up, or down), leading the brain to ignore the image from the misaligned eye, which reduces vision over time.

Anisometropic: Occurs when one eye has a significantly different prescription than the other, causing the brain to favour the clearer eye and suppress the blurrier one.

Ametropic: High refractive errors in both eyes blur vision, preventing the brain from developing normal sight, even though the eyes are aligned.

Meridional: Uncorrected astigmatism blurs vision along certain directions, and the brain gradually ignores those blurred orientations.

Deprivation (form deprivation): Vision is blocked or reduced in one or both eyes (e.g., from congenital cataract or droopy eyelid), disrupting normal visual development.

Combination: More than one type of amblyopia may occur simultaneously.

Idiopathic: A rare form where reduced vision occurs without an identifiable cause, even after a thorough eye exam.

Signs and Symptoms of Amblyopia

In many cases, amblyopia may not have obvious signs, which is why early eye exams in children are critical for detection and treatment.

Reduced vision in one or both eyes: vision may be noticeably weaker in one eye compared to the other.

Poor depth perception: difficulty judging distances or seeing in three dimensions.

Eye misalignment (in some cases): one eye may turn in, out, up, or down (strabismus), though this is not always present.

Squinting or closing one eye: Often to see better, especially in bright light or when focusing on distant objects.

Tilting or turning the head: to favour the stronger eye and compensate for weaker vision.

Difficulty reading or focusing: especially in children, they may skip lines or have trouble recognising letters.

Delayed visual-motor coordination: including trouble catching balls, navigating stairs, or hand-eye coordination tasks, clumsy or frequent tripping/falling.

Risk Factors for Amblyopia

Strabismus (eye misalignment): Eyes that turn in, out, up, or down increase the risk.

Significant refractive errors: Large differences in vision between the eyes (anisometropia), or high levels of near-sightedness, far- sightedness, or astigmatism in one or both eyes (ametropia).

Deprivation of visual input: Conditions that block vision, such as congenital cataracts, droopy eyelids (ptosis), corneal opacities, or prolonged eye patching.

Family history: A family history of amblyopia or strabismus increases susceptibility.

Premature birth or low birth weight: These can be associated with a higher likelihood of eye disorders, including amblyopia.

Managing Amblyopia

1. Comprehensive Eye Examination

Early diagnosis is key. Optometrists check the health of the eyes, visual acuity, eye alignment, refractive errors, and binocular vision to identify the type and severity of amblyopia, if present.

2. Correcting Refractive Errors

If a refractive error is found, prescription glasses or contact lenses are provided to correct this. In many cases, vision improves simply by ensuring the eyes can see clearly.

3. Occlusion Therapy (Patching)

Covering the stronger eye for a prescribed number of hours each day encourages the brain to use the weaker eye, improving visual acuity. Regular follow ups are required to monitor visual development.

4. Atropine Eye Drops

Used as an alternative to patching but equally as effective, the drops work to blur vision in the stronger eye, encouraging use of the amblyopic eye. This is typically offered for children who resist patching. Regular follow ups are required to monitor visual development.

5. Vision Therapy

A structured programme of exercises designed to improve eye coordination, focus, and binocular vision. At For Eyes Optometrist, we offer vision therapy arranged in groups of eight-week sessions for both children and adults. Exercises are tailored for practice both at For Eyes Optometrists and at home.

6. Referral for Specialist Care

For complex cases (e.g. severe strabismus, congenital cataract), the optometrist may collaborate with a paediatric ophthalmologist.

FAQs

Does amblyopia ever go away?

Amblyopia usually does not go away on its own. If left untreated during childhood, the reduced vision in the affected eye can become permanent.

However, early detection and treatment can often improve or even fully restore vision. In older children and adults, treatment may still help, though improvements are typically slower and less dramatic.

This is why routine eye exams in early childhood are so important, because the earlier amblyopia is addressed, the better the chance of achieving strong, healthy vision.

When is it too late to treat amblyopia?

Amblyopia is most effectively treated in early childhood, ideally before age 8–10, when the brain’s visual system is still developing. After this period, improvements are still possible, but recovery is generally slower and less complete.

This is why routine eye exams and prompt treatment are so important, because they give children the best chance for strong, balanced vision.